USDY’s “Dumb Contract” Bridge between Paper and Blockchain

Here’s one way you can think about RWAs.

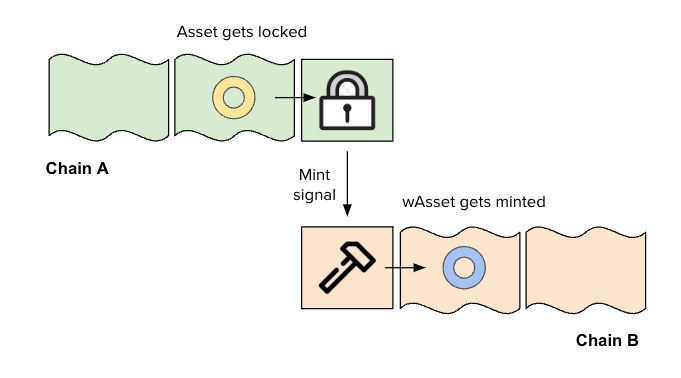

In the blockchain world, you have assets that sit natively on some chain or another. If you want to use your Bitcoin in an Ethereum or Solana protocol, you have to find a way to “bridge” it or “wrap” it from where it lives natively to some new blockchain. After you’ve done that, your Bitcoin can interoperate with whatever protocols exist on that new chain.

You can think of “real world assets” as sitting natively on a chain called “paper”. Really it’s more complicated than that. The title to a single-family home in the United States isn’t just a paper object. It’s sitting on the “paper rails” of some United States legal framework. But by virtue of being on those rails, it can interoperate with a “mortgage agreement” (which is also a paper thing) and then you can raise money.

Obviously there are a whole bunch of “protocols” that already exist on this paperchain and we call that a financial system. If you really want to extend this metaphor, you can argue that every sovereign nation’s laws create their own paperchain, and that we’ve already sort of learned how to bridge assets and interoperate across these different paperchains.1

You can think of crypto’s “real world assets” sector as trying to solve a novel set of bridge problems. How do you bridge assets from paperchain to blockchain, so they can interoperate with the protocols we have in DeFi?

The “Dumb Contract” Bridge

As we’ve discussed previously on the Stableyard, treasury bills have been an early target for tokenization in the RWA space.

Ondo Finace’s USDY is one such attempt, and it’s a unique one. Most projects target Accredited Investors and Qualified Purchases, which you can think of as individuals and asset managers of reasonable means. USDY has chosen a different option under SEC regulation, and targets non-US retail. So how does USDY work?

Returning to this bridge analogy, most cross-chain bridges work through a process of “locking and minting”. You move the asset into a specialized bridge contract on Chain A, where it is “locked in place” and ceases to circulate on Chain A. Chain B then mints a new version of the asset. That new version is free to move around Chain B, until the asset owner wants to bridge it back. The asset on Chain B is then burned, and the asset on Chain A is “unlocked”.

Ondo’s USDY does something sort of similar. And because Ondo has been transparent, we can actually see how it works. Both the smart contract that governs the USDY token and the “dumb contract” that governs Ondo USDY LLC are available to review. Below is a dive into the “dumb contract”, to explain some of the features of USDY’s setup.

SPVs and Smart Contracts

In the TradFi world, using a “Special Purpose Vehicle” (SPV) is about the closest you can get to using a smart contract.

An SPV is basically a legal entity dedicated to housing assets, with a very tight set of rules on how assets move around that SPV. Much in the way a smart contract is basically an account with rules on top of it, an SPV is basically a shell company with rules on top of it.

For USDY, Ondo USDY LLC is its central SPV.

In our bridge metaphor, this LLC is where real world assets are “locked” before they are bridged on chain. USDY’s Tokenized Credit and Security Agreement (“CSA”) details the rules surrounding the SPV. It exists to buy, sell, and hold assets in order to create USDY Tokens. It does very little else. Section 8.06 is the “No Other Business” section of the CSA, specifying that Ondo USDY LLC “shall not engage in any business other than undertaking the transactions contemplated by this Agreement…”.

Because there is no real automation on paperchain, SPVs operate on the oldest form of automation in the book, also known as “hiring someone else to do it”. SPVs will hire and pay some form of “Agent” to handle things like wiring funds, preparing reports, managing bank accounts, and so on. One of the advantages of smart contracts and “end-to-end tokenization” is that you will no longer need to pay people to do this sort of thing.

USDY employs Ankura Trust Company as “Collateral Agent” and “Verification Agent”, and their contractual relationship is also detailed in the CSA. Ankura does not appear to be an affiliate of Ondo at a glance, and has a long history of performing roles like this across various kinds of trusts.

What Assets Get Locked?

My “dumb bridge” analogy becomes fuzzy around the edges here, because USDY is something more nuanced than a wrapped US Treasury Bill. As I read the CSA, USDY is some part overcollateralized stablecoin and some part tokenized treasury bill, and it sort of depends how Ondo uses it. If it was really analogous to a bridge, people would park their T-Bills with Ondo. Instead, the system works with cash.

Here’s the basic flow of minting USDY:

Non-US person gets KYC’d with Ondo.

Non-US person lends dollars to Ondo USDY LLC in accordance with the relevant legal docs, sending those dollars to the LLC’s “Operating Account”.

Ondo USDY LLC airdrops tokens to non-US person.

Ondo USDY LLC takes the dollars it was lent and uses them to buy “Permitted Assets”.

Permitted Assets are detailed in the CSA’s Exhibit 1 and are pretty straight-forward. Basically they’re either Treasury Bills2 or cash in a checking account.

As we’ve learned from the SVB collapse, it matters where you bank. The CSA has some funny capitalized terms around that. It defines “Well Capitalized Banks” and “Adequately Capitalized Banks” based on capital/equity/leverage ratios. If the LLC is banking with an Adequately Capitalized Bank, it gets slightly dinged! More on that later.

What About Interest?

So we have the basic flow down: You give Ondo money, Ondo gives you a token, Ondo buys treasuries.

Where’s the yield?

As per the CSA, USDY accrues interest daily at the “Variable Rate”. Ondo publishes that Variable Rate monthly, on ondo.finance.

Historically, the rate has been very competitive versus comparable products. But the Variable Rate is defined as any number between 0% and 10% as determined by Ondo USDY LLC “in its sole discretion”. While this may seem like too much freedom, there are plenty of good faith, practical reasons to design it this way.

The Variable Rate is set in advance for the calendar month, and there are a lot of unknowns at that time. What will the precise mix of cash and treasuries be over the month? Will there be a lot of minting/redeeming activity for the LLC? Will treasury yields change over that time? What will trust expenses be?3

Ondo has to set something it is sure it can pay, and there is competitive pressure to keep the yield high anyway. There could also be regulatory changes that force Ondo to shut the yield off.

So there’s the basic flow of interest: The assets spit off a yield, Ondo pays holders its chosen variable rate, Ondo pays fees and expenses. And the rest goes to Ondo’s equity.

Equity?

Earlier, I described this structure as “overcollateralized”.

The structure has two ways of measuring this, and they approach the problem from different vantage points. Both amount to some form of additional lender protection.

The more straight-forward approach is an Asset-To-Debt Ratio. Basically, you perform a daily check of the ratio between: 1) the market value of the assets + cash and 2) the face value of all the USDY tokens. If that’s less than 100.5% (a 50bp buffer) for long enough, then the deal is in default.

In this ratio, the value of cash held at “Adequately Capitalized Banks” is 98 cents-on-the-dollar, which is something!

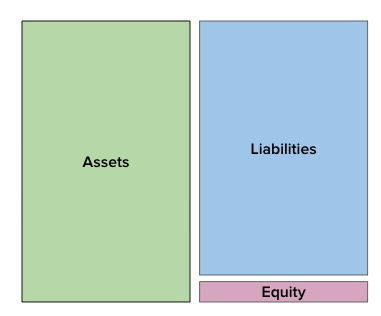

The second approach is an Equity Covenant.

SPVs still have “owners”, they have boards, they have groups with control rights and upside economics. In the CSA, Ondo Finance is referred to as “indirectly controlling” the Borrower, and as making capital contributions to the Borrower. The relationship between Ondo Finance and the SPV would be characterized in the Limited Liability Company Agreement, which is not one of the publicly available docs. But we can think of them as the equity here, providing initial capital contributions and receiving the leftover economics described in the prior section.

The CSA has a capitalized term for “Equity”. A simplified view of it is:

Capital Contributions - Actual Distributions + Unrealized Gains - Unrealized Losses.

This is a good means of capturing what the equityholder’s remaining interest is in the SPV. Under the CSA’s “Additional Covenants” section, the Borrower must maintain 3% Equity as defined above, versus the outstanding amount of USDY Tokens.

3% is a higher number than 0.5%, so at first this looks like stronger protection that the Asset-To-Debt Ratio. But that metric considers the market value of the Treasury Bills. It’s useful to have one metric that is more “mark-to-market” focused and one that is more accounting-y.

In Closing

There’s a lot of other intriguing stuff in here that I didn’t mention. We didn’t touch on the “burning and unlocking” side of the bridge, or on defaults and remedies, or the Fixed Basis Form vs Native Form that USDY comes in. If you aren’t too intimidated by legalese, it can be interesting to take your own spin through. Documents like these are hard to come by if you aren’t in TradFi and this is how the sausage is made.

Also this is not investment advice. I need to put that somewhere right? Who knows. It’s also not tax or legal advice, or marital advice, or nutritional advice, or anything like that. I would never presume to tell you what to do.

In this view of blockchains and “paperchains”, they’re a system for recognizing property rights foremost. A quirk of contract law is that plenty of contracts are governed by New York Law even when the assets and parties involved have nothing to do with New York or even the United States. In this now very extended metaphor, this is sort of like saying “we’re putting this on New York paperchain” so it can plug in to the “judicial rails” that already exist there.

“Treasury Bills” is a capitalized term, defined as “instruments of indebtedness issued by the United States with that mature within one (1) year from their respective settlement dates”.

It does say “with that”, which is a very minor typo. Maybe they’ll catch it for the next amendment!

A lot of these unknowns are probably pretty low risk, and solved for through timing. I think there is time between when the LLC receives cash and when it actually needs to start accruing interest on new tokens, which is a valuable buffer. Treasuries don’t float, so you know what the ones on balance sheet will be paying you. Ankura’s fees and Ondo’s fees are known, but there are often minor unforecasted expenses and reimbursements or whatever.